Important Definitions

Enslaved: a person held in slavery or bondage.

Enslaver: a person or institution that forces others into enslavement

Rural Slavery: the practice of enslaved people living and labouring in rural areas, usually on farms or plantations.

Urban Slavery: the practice of enslaved people living and labouring in urban areas, like towns or cities, often performing skilled labour or domestic tasks.

Slavery is the practice of forced labour and restricted liberty. Slavery has been in The Bahamas from its beginning in European history. Prior to European settlement of The Bahamas, the Lucayans were taken away by the Spanish for slave labour in other Spanish settlements like Hispaniola and Cuba. The Bahamas was left virtually empty of any people. In 1648, when British settlers permanently settled in The Bahamas they brought enslaved people with them. As the colony’s population grew, so did the slave population. Urban slavery and rural slavery both occurred in The Bahamas.

Rural slavery in The Bahamas has a unique history. Many of the enslaved had access to freedom that urban enslaved did not have. Slaves on rural plantations were allowed to engage in subsistence farming and yard gardens. Some rural plantations did not have a Master or Overseer living on them, giving slaves a space away from watchful eyes. Undoubtedly, enslavers allowed their enslaved to provide for themselves because it allowed enslavers to provide less subsistence to their enslaved labour force.

The urban environment of Nassau, and largely New Providence, show how the connections the enslaved fostered helped them escape and produce a place where running away was frequent. Urban centres were prime locations for information to be passed among individuals. Urban slavery allowed enslaved people more opportunities for connections as mobile people like maroons, sailors, and the enslaved were everywhere. Whether enslaved people were being hired out for a job or carrying out tasks for their master, they might have stopped at marketplace or by the well and gossiped with their fellow enslaved; all these encounters led to a wider social network which led to freedom more often than their outer island counterparts. Urban enslaved had mobility and access to the information in ways rural enslaved did not.

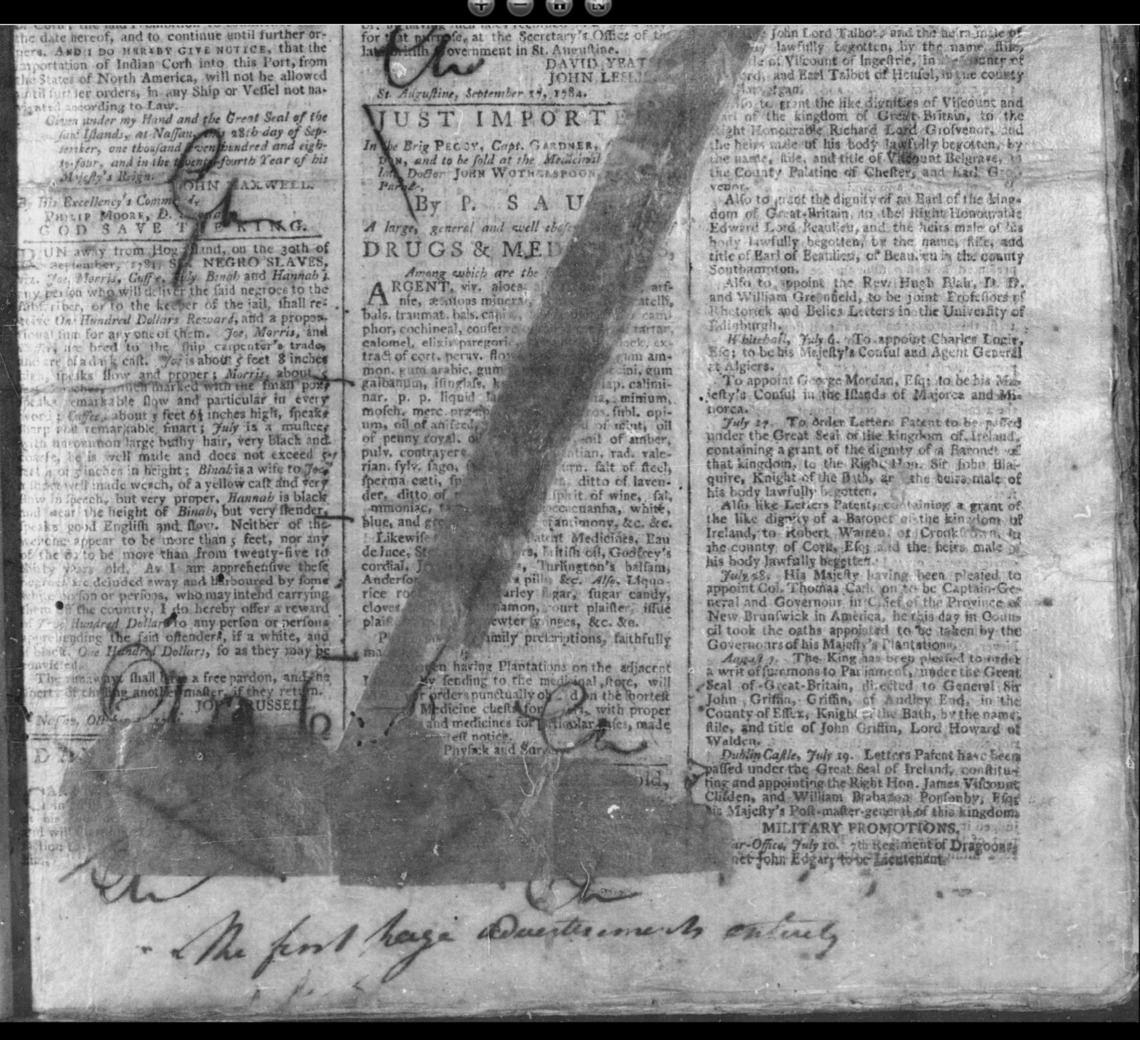

Above: Run away from Hog-Island

These runaway slave advertisements show the life of enslaved in urban and rural areas in The Bahamas. In the late 18th century, Dr. Johann Schoepf observed that Bahamian families in New Providence lived on the returns of their plantations and the work of their slaves.1 Towns and cities as urban centres held a great need for labour which enslavement could provide.

The geography of The Bahamas might cause historians to think about rural and urban slavery existing on multiple different islands. While Nassau was the urban centre of New Providence, and by extension The Bahamas, other islands like Crooked Island and Great Inagua had ports where trading occurred during this time, thus creating an economic urban centre in those locations.

Look At The Map Below to See Locations of the Enslaved Mentioned

Marronage

The term maroons refers to people who escaped slavery to create independent groups and communities on the outskirts of slave societies. Scholars generally distinguish two kinds of marronage, though there is overlap between them.2

Petit marronage refers to a strategy of resistance in which individuals or small groups, for a variety of reasons, escaped their plantations for a short period of days or weeks and then returned.

Grand marronage refers to people who removed themselves from their plantations permanently. Grand marronage could be carried out by individuals or small groups.

Historian Karen Cook Bell says, fugitivity is a revolutionary act of resistance. Thus engaging in any type of fugitivity was something to be lauded. Fugitivity is understudied in The Bahamas. Lack of study on marronage in The Bahamas has led me to look at similar locales and situations for definitions that could fit such a unique place.

Historian Sylviane A. Diouf’s paradigm shift beyond petit and grand marronage to hinterland and borderland marronage fits with the scope of this study. Shifting the focus from the duration of an escape to geographical location allows for maroons’ voices to speak in a new way.

Borderland marronage refers to people who lived in wild land that bordered farms, plantations, cities, and towns.

Hinterland marronage refers to communities far away from settled areas that were hard to reach, usually due to difficult terrain.

Runaways were creating what Historian Stephanie Camp calls a ‘rival geography’ for themselves with their fugitivity. Hence Bahamian maroons could be labelled as engaging in petit, grand, and borderland marronage.3

Notes

-

Dr. Johann David Schoepf, Travels in the Confederation 1783-1784, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia: W. J. Campbell, 1911), 263. ↩

-

Marjoleine Kars, “Maroon and Marronage,” Oxford Bibliographies, August 2016. Historians have had a long debate on differences between a runaway and a maroon. The enslaved would not have cared or made such a distinction therefore I do not find it necessary to do so here. ↩

-

Karen Cook Bell, Running from Bondage: Enslaved Women and their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 14-15; Sylviane A. Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of American Maroons, (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 5; Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 6-7. ↩