Newspapers

In 1784, regularly printed news began in The Bahamas. The first newspaper was The Bahama Gazette. It was later in competition with The Royal Gazette, and Bahama Advertiser starting in 1804. The Bahama Argus would start printing in the colony in 1831. The frequency of the publication of each of the newspaper changed over time.

The Bahama Gazette was printed by John Wells in Nassau, New Providence at his printing office on George Street. The newspaper’s motto was “nullius addictus jurare in verba magistri” which means “not bound to swear by the words of a master.” The Bahama Gazette would changed hands by 1813 to John Traub and Neil McQueen. Their printing office was located on Fredrick Street.

The Royal Gazette, and Bahama Advertiser was printed by Robert Willson in Nassau, New Providence at his printing office on Market Street. In 1813, The newspaper was taken over by N. McQueen & Company. Their motto was “nil ficte foede aut intemperanter” which means “Nothing fake, foul or intemperate.”

The Bahama Argus was printed by George Biggs in Nassau, New Providence at his printing office.

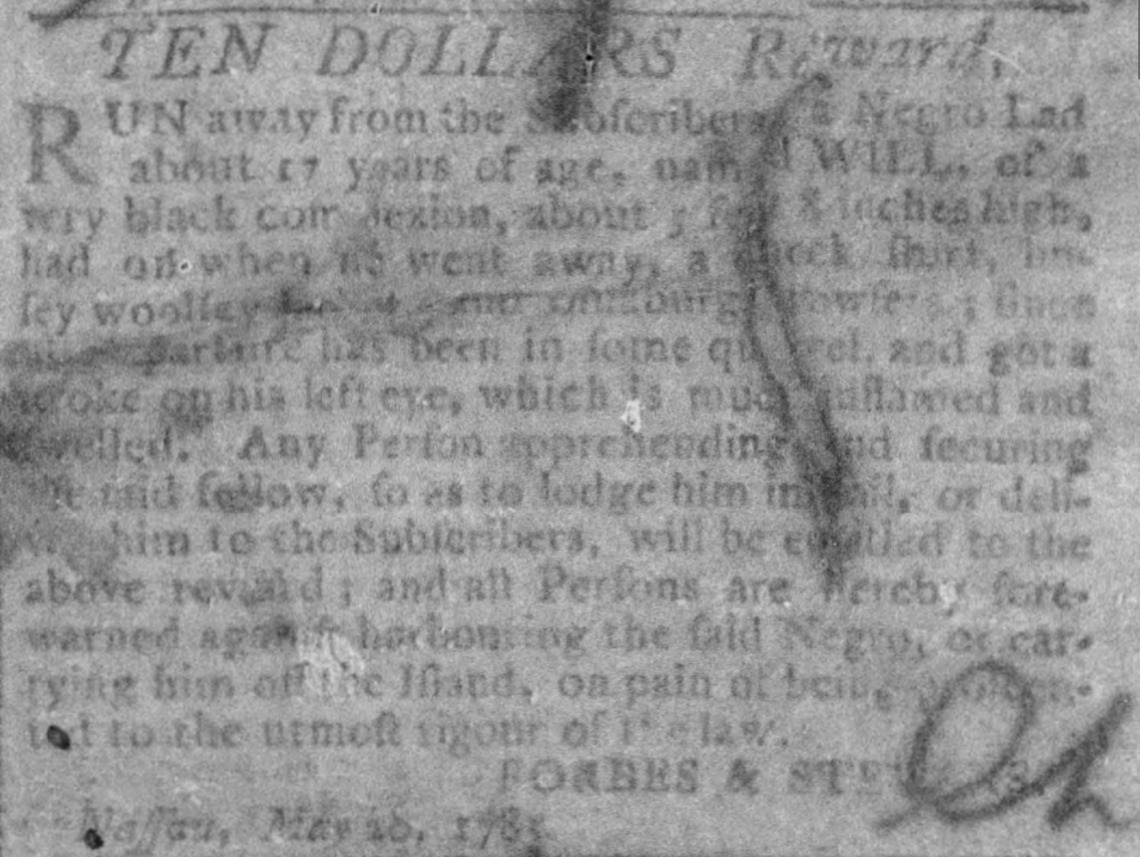

Above: Run away… a Negro Lad

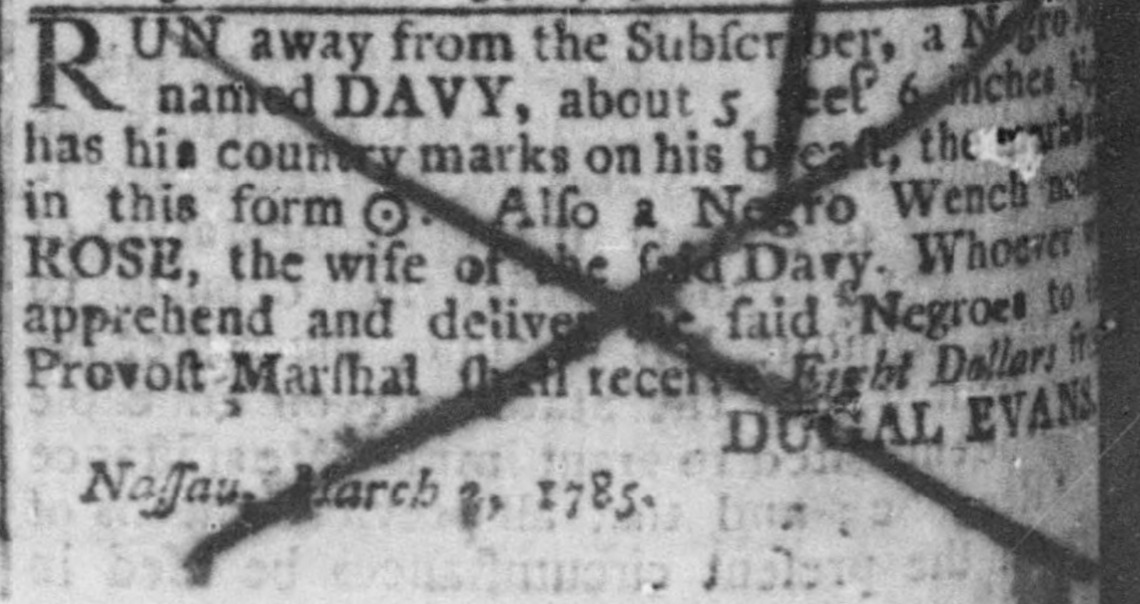

Runaway Advertisements

In The Bahamas, enslaved people ran away. Those who were gone for more than 14 days were deemed outlaws, and owners had to advertise them in “usual public places.”

A 1767 Act indicated that enough enslaved people in the colony ran away for certain restrictions and rules to be put in place against people of colour. Prior to the newspapers, runaway advertisements were published at Vendue House, which was the marketplace.

A lot of information can be observed when studying runaway slave advertisements. You can see who is running away, what they looked like and carried with them, where are they running away from and where they are going.

Many patterns can be observed when looking at runaway slave advertisements. The wording and language of advertisements can indicate many things. One common pattern shows that the enslaved had a strong knowledge about the workings of the colony. Another pattern shows that enslavers put a higher emphasis on keeping their female enslaved over their male enslaved. Female advertisements usually ran longer in the newspaper than their male counterparts. Runaway slave advertisements also show that many enslaved who ran away in Nassau were ‘well known about town.’

Above: Run away… a Negro Man

A White contemporary of the time period, Daniel McKinnen, described a sale of enslaved people in Nassau. He observed, “on the neck of each slave was slung a label specifying the price which the owner demanded, and varying between two and three hundred dollars according to age, strength, sex, &c.” McKinnen remarked that the “cargo “was comprised of numerous enslaved persons from different nations speaking different languages “unintelligible to each other.”1

Notes

-

McKinnen, A Tour Through The British West Indies, 218-219; Daniel McKinnen was a White British traveler who wrote about his tour through the British West Indies. ↩