Urban and Rural Slavery

Under construction

Historians have not deeply studied the unique example of runaway slaves in The Bahamas or looked specifically at urban slavery in Nassau, New Providence. Instead, they have conflated the urban and rural forms of enslavement in The Bahamas, providing little distinction between those enslaved in the outer islands versus those enslaved in New Providence. Urban and rural slavery were both practiced in The Bahamas. While The Bahamas was not a plantation society, in the late 18th Century, Dr. Johann Schoepf observed that families in New Providence lived on the returns of their plantations and the work of their slaves.1 Towns and cities as urban centers held a great need for labour which enslavement could provide. Scholars such as Pedro Welch, AJR Russell-Wood, and BW Higman have shown that urban slavery was consistently practiced outside of the United States.

Rural slavery in The Bahamas has its own unique history. The enslaved in rual areas had access to certain freedoms that the urban enslaved could not experience. Slaves on rural plantations were allowed to participate in subsistence farming on their own time; both genders engaged in the farming. As archeological excavations have revealed the enslaved supplemented their protein from wild species, usually shellfish, fish, and conch which indicates that provisions were not enough to sustain them. Many enslaved had yard gardens as well, though these were “highly gendered spaces” dominated by women. Enslavers allowed their enslaved workers to provide for themselves through these means, undoubtedly because it allowed them to provide less subsistence to their enslaved labour force.2

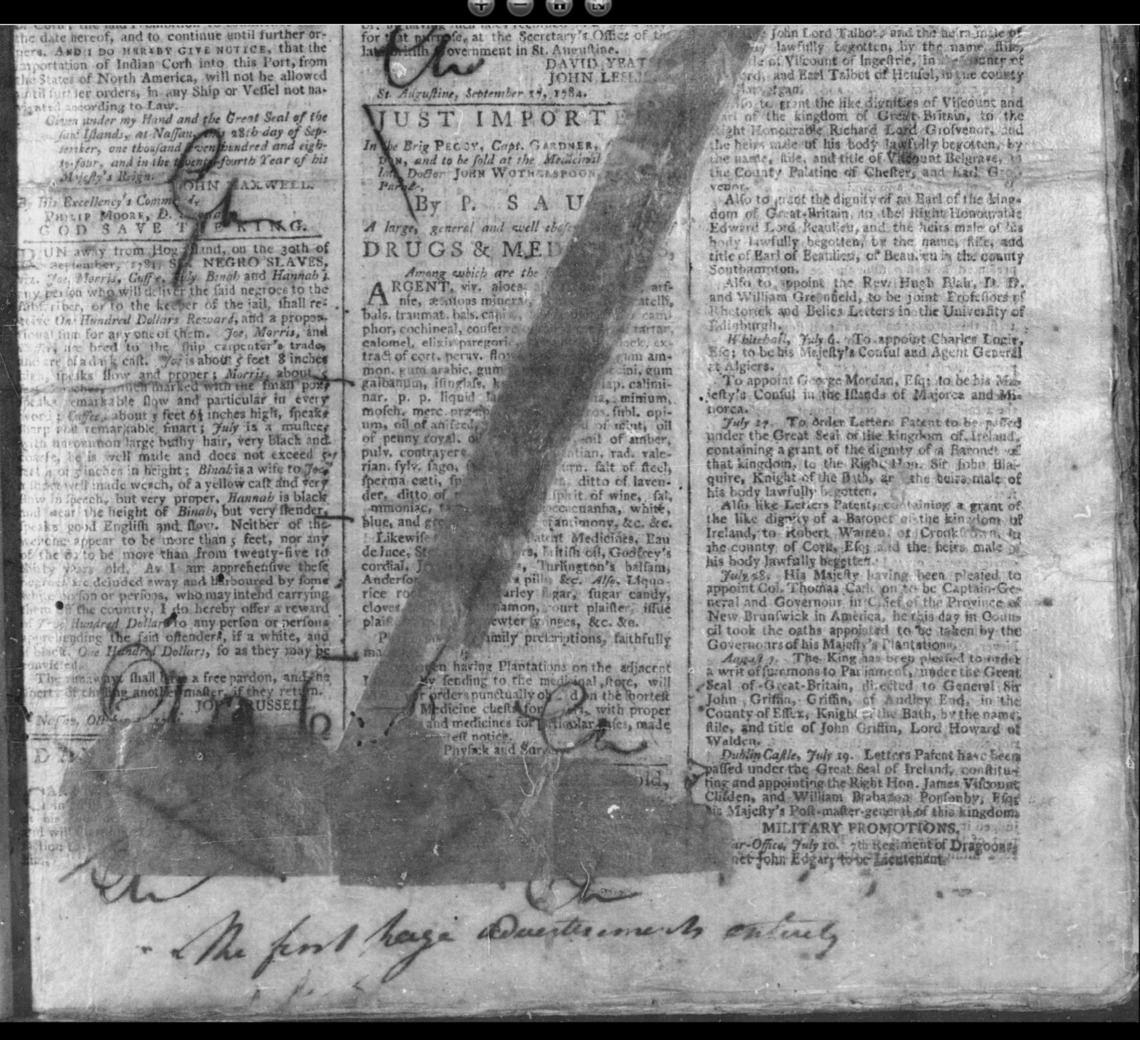

Above: Run away from Hog-Island

Urban slavery needs to be examined to show how the connections the enslaved fostered helped them escape and produce a place where fugitivity was frequent. Urban centers were prime locations for information to be disseminated among individuals. Nassau was a center for mobile people to travel to and through. The urban environment of Nassau (and largely New Providence) allowed enslaved people more opportunities for connection as mobile people like maroons, sailors, and the enslaved were everywhere. Whether enslaved people were being hired out for a job or carrying out tasks for their master, they might have stopped at marketplace or by the well and gossiped with their fellow enslaved; all these encounters led to a wider social network which led to freedom more often than their outer island counterparts. The growth of enslaved labour in towns is directly related to urban development through the Americas and this applies to The Bahamas as well.3 Urban enslaved had mobility and access to the information in ways rural enslaved did not.

The geography of The Bahamas might cause historians to think about rural and urban slavery existing on multiple different islands. While Nassau was the urban center of New Providence, and by extension The Bahamas, other islands like Crooked Island and Great Inagua had ports where trading occurred, thus creating an economic urban center in those locations.

Runaway Advertisements

The enslaved who were gone for more than 14 days were deemed outlaws, and owners had to advertise them in “usual public places.” A 1767 act indicated that enough enslaved people in the colony ran away for certain resistrictions and rules to be put in place against people of colour. The first newspaper, the Bahama Gazette did not come to The Bahamas until 1784, so the advertisements were usually placed at Vendue House, which was the slave marketplace.

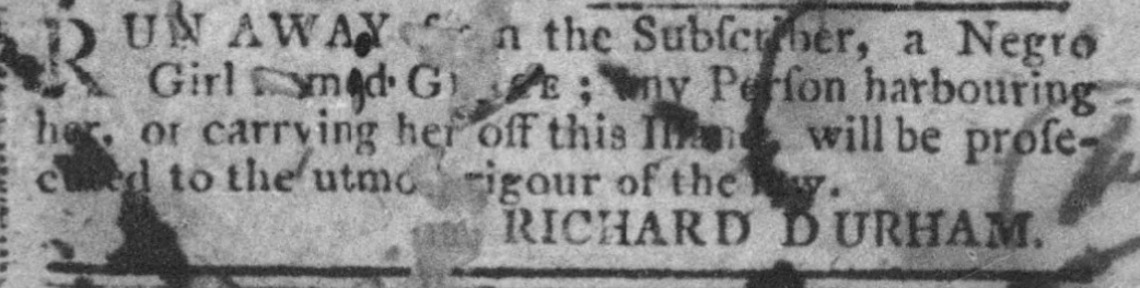

Many patterns become observable when looking at runaway advertisements. The wording and language of various advertisements indicate fastinating things. Common patterns show that the enslaved had a strong knowledge about the workings of the colony and the wider world. It appears that masters put a higher emphasis on retaining their female slaves over their male slaves as female ads usually ran longer in the newspaper than their male counterparts. The advertisments show that many enslaved who ran away in Nassau were ‘well known about town.’

Above: Run Away… a Negro Girl

White contemporary Daniel McKinnen described a sale of enslaved people in Nassau: “On the neck of each slave was slung a label specifying the price which the owner demanded, and varying between two and three hundred dollars according to age, strength, sex, &c.” He remarked that the “cargo “was comprised of numerous enslaved persons from different nations speaking different languages “unintelligible to each other.” McKinnen described the “benevolent masters” of those purchased, saying how “delighted” the enslaved people were with their “kind treatment” and change in situation. 4

Look At The Map Below to See Locations of the Enslaved Mentioned

Notes

-

Dr. Johann David Schoepf, Travels in the Confederation 1783-1784, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia: W. J. Campbell, 1911), 263. ↩

-

Craton and Saunders, Islanders in the Stream: A History of the Bahamian People: Volume One: From Aboriginal Times to the End of Slavery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992), 188; CO 23/67/103-115; Paul Farnsworth, “Archaeological Excavations at Promised Land Plantation, New Providence,” Journal of The Bahamas Historical Society 16, (1994): 27; Paul Farnsworth and Laurie Wilkie, Sampling Many Pots: An Archaeology of Memory and Tradition at a Bahamian Plantation (Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 2005), 159. Laurie A Wilkie, “House Gardens and Female Identity on Crooked Island,” Journal of The Bahamas Historical Society 18, (1996): 36; Douglas Hall, “Slaves and Slavery in the British West Indies,” Social and Economic Studies 11, no. 4 (1962): 314. ↩

-

Mariana Dantas, Black Townsmen: Urban Slavery and Freedom in the Eighteenth-Century Americas (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 68-69. ↩

-

McKinnen, A Tour Through The British West Indies, 218-219; Daniel McKinnen was a White British traveler who wrote about his tour through the British West Indies. ↩